Content Warning – This article discusses and depicts racist content in regards to Chinese people and Chinese-Americans, Black Americans, racial slurs, stereotypes and caricatures in comics. There are mentions of police shootings and lynchings. This also discusses the merits of preserving art with racist content.

Special thanks to Professor Jonathan Gray of the School of Visual Arts NYC. Without his professional and academic background within comics, the questions I hoped to ask would not have been possible. Please check out his site at www.jongraywb.com for more information on him and his work.

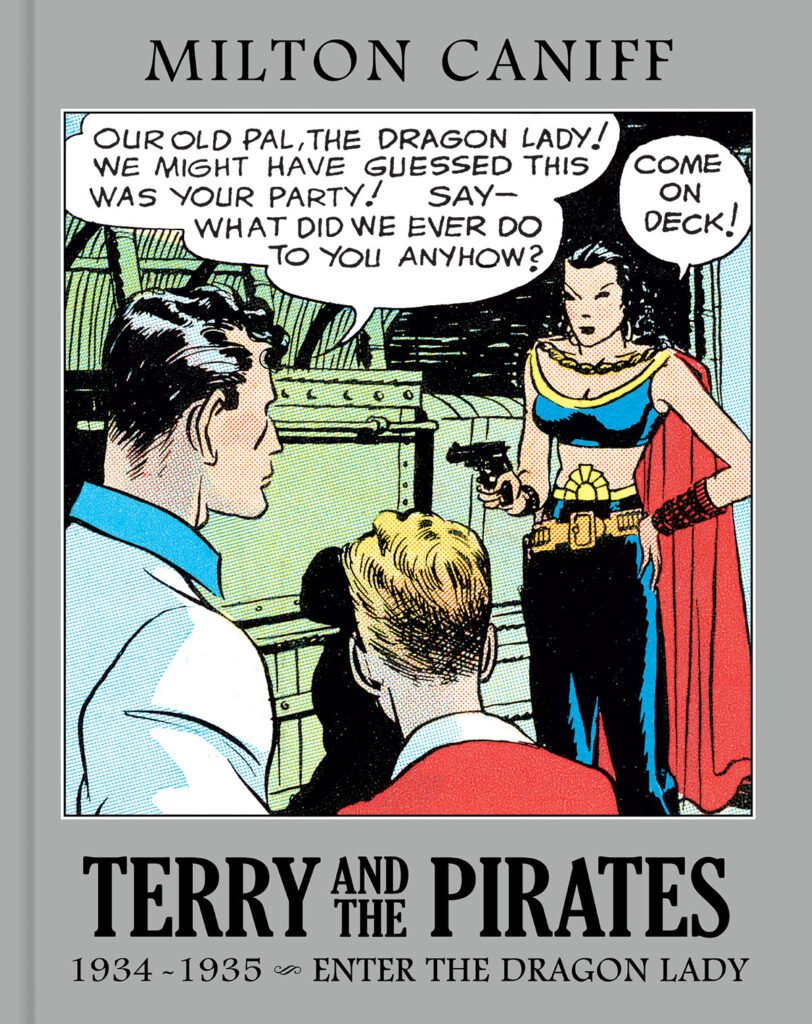

This interview is going to be different than the others I’ve posted. I didn’t want it to be. Discussing the new, oversized Terry and the Pirates: The Master Collection with its spectacular new coloring was meant to be a standard interview. The Library of American Comics co-founder and editor Bruce Canwell did fit my preferred subject – bringing in an expert to talk about their craft in detail. And he was pleasant, thoughtful, and took time to answer my questions fully and thoroughly. As I happen to really enjoy Terry and the Pirates, this was great. Everything was going fine, right up until I asked how he felt about the responsibilities of publishing an older comic with racist content. At that point, it all went very very wrong.

Archiving material for future preservation is, evidenced by roughly everything I’ve written on this blog, something I find critically important. But I’m also aware that while Terry and the Pirates is a masterwork of a comic, the first two years of this strip specifically threw around racial slurs, caricatures, mocking portrayals and stereotypes consistently and without irony. The historical value of Terry and the Pirates is undeniable, as is Milton Caniff’s value an artist and the work he produced. Just as undeniable is its racism towards Chinese people in its Chinese setting.

Some of these elements persist throughout the entirety of Caniff’s run, even as his research into China grew more detailed and the characters more three-dimensional. But there were holdovers such as one of the protagonists, the pidgin-English speaking, bucktoothed, slant-eyed Connie, who would look right at home in Tokio Jokio.

When conducting this interview, I was operating off of the assumption that the numerous racial slurs and the character of Connie would be considered racist as a given. That despite the comic being great, even the character himself having value, both were just straight up racist. With that in mind, we could talk about how readers could accept this knowledge and make the choices they were comfortable with. As it turns out, this was not the case.

I asked Canwell for his thoughts on how to responsibly publish a racist comic for archival purposes. Specifically in regards to the effects of it on readers today, and the way we can tackle the level of racism that exists within comics (particularly older ones.)

His answers were dismissive of the racism of the time, chalking it up to how it was just stereotypes and shorthand rather than something racist. He at no point addressed how readers today might be affected by the material on a personal level, particularly Chinese-Americans, who as it happens, also read comics.

Some of his points echoed Comicsgate, specifically regarding comics being escapism for the time rather than “musing on societal issues” – while at various points discussing the effect that World War II had on the strip, Caniff’s political motives in supporting the US military, his condemnation of the Japanese invasion of China, his work on writing some of the most three dimensional women in comic strips – without any self-awareness of the shift.

I seriously considered not publishing the article at all, particularly with Comicsgate material in one of his answers. I had no desire to even appear to condone the content.

Then I remembered why I had asked about race to begin with – to help people make a decision on whether or not they would pay money for a comic strip with a lot of racist stuff in it. It’s an expensive comic, but a great one, and it does have more components during its twelve year run than just its racist ones. I did pre-order its first three models in a subscription, after all. Condemning it wholesale isn’t something I’m comfortable with, but I’m never going to blindly recommend it.

As a comics historian who has written on Caniff extensively, I believe Canwell abdicated the opportunity to help people understand ways in which one can responsibly consume media with racist material in it in regards to Milton Caniff’s work on Terry and the Pirates, and comics overall. That abdication is an answer in and of itself for some people.

As such, the interview will be published in its entirety. Scroll down (or use Ctrl + F) to “A Few More Questions…” to see his answers regarding the comic’s racist content.

I do think the questions I asked about reading responsibly were important. Since he did not answer those questions in any appreciable way, and I don’t have the answers of how to respond as a publisher, I’ll give my own from my perspective as a reader. This is the manner in which I choose what to watch, and what not to watch. I’m a straight white male, so I can’t base my decisions off a lived experience from people who are being degraded or demeaned in this way. This is just me, and what I can live with at the end of the day.

It is possible to consume, and enjoy, some racist pieces of media in a responsible way. But it requires being an active participant. Understanding that a blackface joke was one of many indignities to real Black people, that speaking broken English and pulling ones eyes to a slant to imitate an Asian person was demeaning to real Asian people – something that was true then and today – is necessary.

This is not a matter of self-flagellation. It is a matter of being aware of what you’re reading, because what we read affects us, personally and societally. Wil Wheaton, in fact, made a similar point about how comedy affects its viewers, particularly in regards to Eddie Murphy and Dave Chappelle.

As a passive reader, it is very easy to take in what is presented at face value. It’s when somebody looks at Mickey Rooney in Breakfast at Tiffany’s and sees it as “harmless fun.”

We all draw lines for what we’re willing to watch. Perhaps your line is something you don’t like seeing, like gore or racial jokes.

Perhaps it’s what you think would be hurtful to the people closest to you if they were watching it.

Perhaps it’s people involved in its making that have done terrible things.

Perhaps it’s simply the evil that something brought into this world, regardless of the good.

That is a choice that everyone makes: even if they choose not to think about it at all, they’re still making a choice by picking what they take in.

Bill and Ted’s Excellent Adventure has a homophobic slur used as a joke. Rocky has Adrian and Rocky’s first kiss portrayed in a way which does not appear to have enthusiastic consent. I enjoy both of those movies despite their flaws. The Birth of a Nation is an epic movie, with technical achievements and marvels that show a technical vision beyond anything I would ever expect from a 1915 silent film. It is also rightfully credited as causing the reformation of the Ku Klux Klan, and caused a horrific increase in lynchings of Black people across the United States, as well as mass atrocities like The Red Summer.

The Birth of a Nation caused a movement in white supremacists being accepted, elevated, and placed in positions of governmental power. It was a turning point in history. These attitudes, laws and lynchings brought on by a re-energized set of white supremacists continue today. Many of them take the form of police shootings. The movie was also a turning point in film and special effects.

While I enjoy both Rocky and Bill and Ted’s Excellent Adventure, I refuse to watch The Birth of a Nation, regardless of its artistic merit. This is not a personal failing. This is a choice, and one that I am perfectly comfortable making.

I’ve made my choices as responsibly as I know how. I personally have the ability to appreciate Terry and the Pirates as a newspaper comic. I can enjoy the linework, the inking, a great deal of the humor, the romance and tension, and the fight for freedom and justice in the face of oppression, crime and corruption. I do this knowing that Caniff’s treatment of China is (eventually) heavily researched, and (eventually) was treated with a great deal of respect. I purchased a subscription to the first three volumes of the new Terry and the Pirates edition. I also know that it’s so racist for the first two odd years that if I gave the comic to a Chinese-American to read without context and content warnings, I’d justifiably get punched in the face in about two seconds.

This is no different than the case of Ebony White on The Spirit: despite how Will Eisner created some of the most inventive works in comics, Ebony’s portrayal was horrendously racist. But you won’t ever catch me saying Ebony White was an acceptable product of his times – it was racist then and it’s racist now, because Black people and their dignity didn’t start existing in 1954. The harm and hurt that comes from offensive portrayals from the past isn’t somehow less offensive to see just because it was made in the 1940s. Chinese people are no different in this regard, and this is the problem I have in Canwell’s answers regarding a publisher’s responsibility in publishing something like Terry and the Pirates.

The Library of American Comics’ first publication was in 2007, with the first volume of Terry and the Pirates. They have, collectively, had over 15 years (accounting roughly for production time) to consider their responsibility as publishers. They could have considered the affect it would have on real people reading it today, especially with the rise of hate crimes against Asians, American or not, in a number of predominantly white countries – and in the United States specifically.

I hadn’t read every book that the Library of American Comics has produced, but I haven’t seen content warnings of any sort. If they are there, they’re certainly not easy to find. And, naturally following that omission, I’ve never seen a foreword saying that a creator who produced something incredible was, in fact, flawed with explicit words to describe the person or comic – homophobic, racist, transphobic, etc. The words are not used, and they are conspicuous in their absence.

The first volume of the original printing (in a section also written by Bruce Canwell) specifically says that if you look at the character of Connie as a a racist one, you’re missing the nuances of the character. The first introduction, and this interview, do not acknowledge that the two can co-exist – that a work can be fundamentally flawed and still have value. It excuses the racism instead.

My reading of Canwell’s answers in this interview leads me to believe that defending the portrayal of the character of Connie and China was more important than acknowledging real people, not just the abstract ‘comics fan’, who would be personally affected by this strip. The racism, sexism, homophobia, transphobia, and the other implicit or explicitly hurtful ways in which other people, people, thinking and breathing and feeling people and still comics fans too, are affected.

If a piece of media is so fragile that an admission of its racist material shatters its ability to be enjoyed, then the media was not worth the time and effort on the part of the reader. I do not believe this is the case for Terry and the Pirates. I am unsure whether Canwell shares that same faith in the strip.

I present to you now the full interview.

Mr. Canwell, I appreciate you taking the time to speak to me about the new Terry and the Pirates: Master Collection the Library of American Comics is putting together.

To start – what is your role in the LOAC as a whole, and what is your role for this edition of Terry and the Pirates?

Hi, Mathias! Feel free to call me whatever makes you most comfortable, but in my family we don’t stand on formality, so I’ll even answer to “Hey, You.”

That said, let me see if I can answer your question. My title is “Associate Editor,” though I have had full editor credits on some Library of American Comics (LOAC) series. Titles aside, I’m the text guy. Part of LOAC’s reputation stems from the in-depth text features included in most of our books, and I either research and write those, or I edit the work of other writers. In past releases I’ve work with Jeet Heer, Brian Walker, Jared Gardner, Trina Robbins, Bill Watterson, and Jeff Kersten, among others. It’s always an honor to help present their thoughts in the best possible way.

How would you describe Terry and the Pirates to a comics fan who had never heard of the series before?

That’s easy! Milton Caniff’s Terry and the Pirates is the greatest action-adventure newspaper strip in comics history, bar none. It set standards rarely met and never exceeded within the comic strip subgenre, and it was admired by and helped influence a number of talented individuals who went on to become Big Names in film and television as well as in the comics field. Like most enduring creative works, Terry is sui generis – often imitated, but never equaled.

Now that is a glowing endorsement if I’ve ever heard one! But I’m also curious how you would describe Terry and the Pirates as a story. After all, it’s not just fans of Terry who might want this edition to read the story – and I know I have a hard time summarizing it. How would you describe the story of Terry and the Pirates to someone who had never heard of it?

In the simplest view, Terry and the Pirates is one link in a long chain of “boy adventurer” series, a subgenre that spans at least from The Hardy Boys in 1927 to Jonny Quest in the 1960s – and I suppose, if you want to stretch the comparison, to the 21st Century Venture Bros. In my mind, Terry’s closest analogue is Jonny Quest’s Asian episodes, minus their super-scientific content. Both series feature youngsters in exotic lands, accompanied by adult mentors and having exciting adventures that are reflective of their respective time periods. Both feature nefarious villains and lovely women, though Terry has a larger female cast than Quest’s, and Terry’s women play a much more active and important role in the ongoing narrative. Jonny Quest lasted only one season in the mid-1960s, while Terry ran seven days a week from the Depression-era 1930s through the end of World War II in 1946, so there is a far greater depth of story and progression of characterization in Terry than you’ll find in Quest. Finally, though Quest has a certain amount of Cold War sensibility as its series subtext, the geopolitical situation of the period in Terry is more front-and-center – Terry was depicting Japanese soldiers waging war against the Chinese in the late 1930s, at a time when many Americans wanted to isolate themselves and their country by turning away from Nazi and Japanese atrocities in Europe and China.

To sum it up – I think if you like Jonny Quest, you’ll love Terry and the Pirates!

The series was first published in 1934 – a ways back for any comics fan. What led you to older newspaper strips, and this one in particular?

That’s an intriguing question, though I’ll admit it’s one I probably don’t fully understand.

You’ve heard the old saying, “We stand on the shoulders of giants?” That’s something I understood at a pretty young age – as you read interviews with creators you admire, you invariably find them talking about the capital-G Great talents who influenced them. It’s always made sense to me to check out those Greats. Heck, as a kid a Muppet Show episode featured Rowlf the Dog and Lena Horne enthusiastically touting Billie Holiday. I told myself, “If she’s good enough to impress Lena Horne and Rowlf, I gotta find out what this Billie Holiday is all about!” – and today my music library includes over six hundred Billie Holiday songs. Without that tip from The Muppet Show and a willingness to follow up on it, I might never have discovered the fabulous – and tragic – Lady Day.

So – I grew to adulthood understanding that there is a wealth of fantastic material that came before me: books, music, film, TV, essays, and yes, comics. Advances in technology and changes in economic conditions over the years have helped make much of that excellent work available, and I’ve been fortunate to read, watch, and listen to large portions of it.

Specific to Terry, my introduction to Milton Caniff’s work was issue # 1 of Steve Canyon magazine, published in 1983 by Kitchen Sink Press. It didn’t take many issues of the Canyon magazine for me to realize this guy Caniff had it going on – so it was natural for me to reach out and start buying the 1980s Terry collections from NBM Publishing/Flying Buttress Comics. That began an unabashed love of Caniff’s Asian odyssey that obviously remains to this very day.

You answered my question exactly as I’d hoped, so no worries there!

Terry and the Pirates became a foundational part of American comics’ DNA, with Carl Barks, Chris Claremont, and Jack Kirby being just a few examples of titans unto themselves. But looked at outside of its historical importance, what makes Terry and the Pirates worth reading today?

Terry checks all the boxes that make for exciting and rewarding serial adventure fiction. Heroes to cheer and villains to hiss? They’re in there. A vivid, varied supporting cast that weaves in and out of the narrative and who connect with one another in surprising ways? Definitely! An increasingly mature and emotionally-engaging narrative that emerges through a skillful blending of action, conflict, romance, humor? Yes, yes, yes, and yes!

Add in its historical importance and its influence on comics and other forms of visual storytelling and it escapes me how anyone can not realize Terry and the Pirates is a compelling work that repays repeated readings.

The saying “We stand on the shoulders of giants” is a true one – but even among giants, of which I named only a few, Milton Caniff is a Titan. What do you consider to be some of the enduring influences he had on comics and comic strips going forward, not just among his contemporaries but as a whole?

Contemporaneous with Terry, cartoonists Charles Raab wrote and drew The Adventures of Patsy and Alfred Andriola produced the Charlie Chan newspaper strip – as we discuss in Volume 13 of the Terry Master Collection, both men were part of Caniff’s “inner circle,” and it’s arguable whether either man would have landed his assignment without the connection to Milton. Frank Robbins’s excellent Johnny Hazard strip, which began in 1944, is a stylistic kissin’ cousin to Terry and the Pirates. Those are only three examples of the larger school of adventure comics storytelling that emerged as strip creators sought to emulate Caniff’s approach and Terry’s narrative magic.

Heck, the steamy March 1936 Terry sequence that builds into Pat Ryan and Burma’s first kiss is so influential that Amendola duplicated it in a 1939 Charlie Chan continuity, while Warren Tufts borrowed it for his Casey Ruggles strip as part of a story from December of 1949!

And let’s jump over to Marvel Comics. Look at John Romita Sr.’s work – who is one of his primary inspirations? Clearly, it’s Milton Caniff, which Romita himself has enthusiastically confirmed. Amazing Spider-Man # 108-109, revolving around Flash Thompson’s adventures as a soldier in Viet Nam, were a homage to Terry and the Pirates. Even more famously, who hasn’t heard of or read Spider-Man’s “Death of Gwen Stacy” story? Romita grew up a Caniff fan, and one famous Terry story made such an impression on him that decades later it helped him influence the decision to kill Gwen, then an enormously popular character. As he told me in an interview, a portion of which appears in Master Collection Volume 13, “That’s the secret Caniff taught me: kill somebody big, or don’t kill anybody.”

It’s the never-ending creative chain. Even if a comics creator never heard of Milton Caniff, but is influenced by John Romita Sr. (or is influenced by a creator who was influenced by Romita), then that creator is influenced by Caniff, too – and in turn, by every talent who influenced Caniff. “We stand on the shoulder of giants,” though sometimes our vision doesn’t extend downward far enough to recognize all the giants whose shoulders we’re standing upon!

You’ve stated that your six-volume Terry and the Pirates series was done to finally publish Milton Caniff’s run on the series right, but you’re starting from the beginning all over again. What led you to re-release the series when your first edition received Harvey nominations and an Eisner?

Terry and the Pirates was The Library of American Comics’s first project – when we launched it in 2007, the comic strip collection bookshelves were a lot emptier than they are today. We were blazing something of a trail by reprinting a comic strip in large-sized hardcovers, featuring full-color Sunday pages. Terry had never had such a lavish treatment in any of its prior reprinting, so by 2007 standards, we accomplished our goal and did Terry right.

Fifteen years and more than two hundred LOAC releases later, we have grown more experienced, and we discovered exciting new source material. The chance presented itself to do Terry right-er, so we’re seizing that chance.

The Master Collection

One of the biggest selling points of the Master Collection is the newly discovered syndicate color proofs for the Sunday strips. For those unfamiliar with printing methods of the 1930s-40s, what are color proofs?

As the name implies, copies of the finished strips as they’re to be printed are used to proofread many aspects of the finished product. Is the color accurately printing and registering as expected? Are there any spelling efforts that need correction? Anything that might be “off-kilter” can be spotted and fixed, and a revised proof copy gets a final check before the OK is given to go to press.

We’re using a newly-discovered and a nearly-complete set of Terry final proofs to use as the basis of our Master Collection. This offers readers nuances in coloring and a level of detail in the linework and brush strokes that has never before been available in any previous Terry reprinting, including our original release of the series. It’s safe to say that Terry and the Pirates has never looked better than it will in this set of books.

Adding to that question – how on earth did you find them?

One of our primary sources of material and information for many books is the Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum, located on the campus of The Ohio State University. BICL&M, as it’s sometimes abbreviated, is an Ali Baba’s Treasure Cave of comics history, and its staff is thoroughly professional, collegial, and helpful.

The core of their holdings are Milton Caniff’s papers. An Ohio State alumnus, Caniff donated his holdings to the museum decades ago – and Caniff was one of those guys who saved everything! Letters – research – newspaper and magazine articles about Terry, or about him or his family and friends – photographs – awards. Milton kept it all, and he eventually turned it over to his alma mater, all six hundred ninety-six cubic feet of it!

As you can imagine, doing a detailed description of so much material is a Herculean task – so several items had been identified only as “scrapbooks.” During a trip to BICL&M, LOAC Creative Director Dean Mullaney discovered these scrapbooks contained the high-quality Terry proofs. Once he picked his jaw up off the floor, plans for The Master Collection started brewing …

This format is something of a departure from the typical LOAC release, standing 14 inches tall and 11 inches wide for all 13 volumes. What are you doing differently with this format, and how does it change the reading experience?

Actually, it’s less of a departure than you’re indicating – we’ve released a number of similarly-sized books during LOAC’s fifteen years. We did the complete run of Alex Raymond’s beautiful Flash Gordon, with its Jungle Jim topper strip, in a similar format; we did the same with two collections of Cliff Sterrett’s wonderfully wonky Polly and Her Pals Sunday pages.

So we have experience working in this size, and it allows us to present Terry Sunday pages in their “tab(ular)” format – which was the way Caniff drew his Sundays, and the way they ran in newspaper formatted like the New York Daily News – rather than the reformatted “half-page” format (“tabs” were reworked to fit the oblong format of newspapers like the Cincinnati Enquirer, which often ran “halves” of two comic strips on each page of their Sunday comics section).

Originally, Terry and the Pirates had two concurrent stories – one taking place in the Sunday strips (from 12/9/34 to 9/19/36), the other in the six daily strips. After that, the strips essentially merged to one contiguous story.

Your original release dealt with the Sunday/daily split by having the first volume start with the Sunday strips, switching to the dailies, and finally publishing the rest of the comic in chronological order. Will the Master Collection be published in the same way, and why?

In 1934 the artform was still very much in its infancy – there were no hard-and-fast guidelines, no established roadmap to follow when it came to constructing a new comics series.

Cartoonists had to produce their Sunday pages weeks in advance of the daily strips that lead up to them, because of the amount of production work necessary to publish a Sunday. That meant the easiest route to take for the creator of a continuity strip was to tell one story in his dailies and an entirely separate story in his Sundays – Li’l Abner took that approach throughout its run, for example, and Milton Caniff started out that way with Terry, too. Still, the most popular strips at the Chicago Tribune New York News Syndicate that Terry called home were Little Orphan Annie and Dick Tracy. Both those strips knitted their dailies and Sundays into one cohesive narrative.

The decision was made to have Terry follow Tracy and Annie’s fully-integrated approach; one of the artifacts we located and will be reprinting in The Master Collection is a letter from Harold Gray, Annie’s guiding light, responding to Milton’s request for advice on how to achieve a smooth seven-days-a-week story flow. Gray’s response starts by saying, “If I knew the answer to perfect synchronization of dailies and Sundays I’d avail myself of it …” before launching into a really fascinating analysis of how editors viewed the comics they publish.

Given Terry jumps from separate-daily-and-Sunday plotlines to one integrated story running seven days a week, we had to make a choice between two alternatives. Should we print every strip in chronological order, giving the reader one story in six dailies, then interrupt that flow with an installment of a separate Sunday story on the next page, then interrupt that flow by going back to the daily story for six more installments, then lather-rinse-repeat? with the Sunday, and lather-rinse-repeat? Or should we gather together all the standalone-Sundays, followed by all the standalone-dailies, followed by the unified daily-and-Sunday approach once that rhythm gets established?

When we produced our first Terry series, we believed the second choice was the correct one, and we haven’t changed our minds in the intervening fifteen years.

The first Terry and the Pirates release included essays, making-of material, and the history of the comic in each volume. Will the Master Collection have supplementary material in the 12-volume set, or will that all be part of the larger, behind-the-scenes 13th volume?

The Master Collection’s first dozen volumes will feature only the Terry and the Pirates comics. Our text and additional material are gathered together in the thirteenth volume, titled “Odyssey on the China Seas.”

The 13th Volume doesn’t collect the comic strip specifically, instead showcasing behind-the-scenes material. Can you talk about what’s included in that volume?

How about forty thousand words of deathless prose from yours truly? (Could a plug be any more unabashed than that?)

Feeble jokes aside, I’ve written a lengthy essay that examines Milton Caniff’s life and career up to and through his Terry and the Pirates years. This piece describes the effect Terry had on the comics medium of the day – remember, Superman and Action Comics #1 are still four years away when Terry begins in 1934. It also looks at the strip’s effect on the culture at large, as well as how that culture helped shaped the strip in turn. I also “set the historical stage” and discuss major news of the day in order to help provide readers insight into life in the 1930s and ’40s, which I believe helps shed light on some of Milton’s storytelling choices.

My goal in any of my LOAC pieces is to tell an engaging story – a work like this should be interesting, informative, and entertaining, in equal parts. We’ve probably all encountered some comics scholarship that reads like a high school paper turned in for English or History class. I labor to read such articles and I suspect others do, too. That helps keep me working to find ways to make the facts “come alive” for readers. I hope I’m at least somewhat successful in achieving that goal.

Of course, Volume 13 has much more than my text going for it! We have loads of artwork and photos for readers to enjoy, including a provocative portrait of the Dragon Lady that Caniff painted as a gift for director Orson Welles in his pre-Citizen Kane days. One of my favorite photos is of Milton with a baker’s dozen of pretty girls, all hoping to be selected as the model for Caniff’s new character, Nurse Taffy Tucker. We also feature congratulatory cartoons produced to commemorate Terry’s tenth anniversary by talents as varied as Hal Foster, Edwina Dumm, Chic Young, Siegel and Shuster, Hilda Terry, and several others.

By the way, we also have a handful of Terry strips that are not part of the series continuity! Some of these were drawn to support advertising campaigns, or as a public service in support of a good cause. One is a rejected daily that was originally scheduled to run on January 14, 1942, and one is a Christmas strip specially drawn for one of Caniff’s hometown Ohio newspapers that features Terry, Pat, Connie, and Big Stoop stepping off the drawing board and interacting with Milton himself!

Finally, you’ll pardon my pride if I refer everyone to the engraver’s guide for the full-color July 14, 1940 Sunday page we show you in Volume 13. Once it hung in a trendy Manhattan art gallery, but today that original hangs at the top of the stairs in my home!

Milton Caniff released a weekly strip for army newspapers using the character of Burma, also titled Terry and the Pirates. Instead of an adventure strip, the comic was a gag strip with military humor and a signature Caniff woman to heighten morale for the troops. After objections from the syndicate, the strip was re-titled Male Call with a new main character, with just fourteen installments of the Burma strip. Will they be included in the collection in some capacity?

We have a selection of the military-newspaper Terry and the Pirates strips that feature Burma, as well as a selection of Male Call strips – this effort was such an important part of Milton’s War years activity that we’d be remiss if we ignored it. But we have to limit the number of these strips we run – the series is about Terry and the Pirates, not Male Call, after all!

Male Call fans may also be glad to know Volume 13 features several photos of lovely brunette model Dorothy Partington, dressed to play the part of Miss Lace. I also found some great information on the only known Miss Lace fiction not created by Caniff – a play called “A Date with Lace” that was staged at the Dodge City Army Air Field and was quite a hit with the GIs in the audience.

“A Date With Lace” sounds fascinating. Were you able to find the full script for that as well, and if so, will there be a way for readers to read it themselves?

Don’t we all wish! If there’s a script in the Caniff papers at BICL&M, we’ve yet to find it. I learned of this production by reading coverage in an Army camp newspaper called the Boot Hill Marauder, and everything we know about the production comes from that source – which is more than has been made available in any previous work devoted to Terry that I’ve seen, I might add …

[Editor’s Note: the complete run of Male Call, with the Burma and Miss Lace strips, is available from Hermes Press at this link.]

A Few More Questions…

Terry and the Pirates‘ largely Chinese setting naturally means a number of non-American, non-white characters, and the time period in which it was published meant different sensibilities regarding racist stereotypes and caricature towards any people of color. While not a constant, and something that Caniff seemed to work to gravitate away from over time, racism is a factor in the series that can’t be ignored.

The culture of comics has changed drastically, with an understanding that the material was hurtful and racist to groups at the time, not just in hindsight. The way that we read historical pieces with a modern lens remains something that we are reckoning with societally. And in the present day, outside of the comfort of comics, Asian-Americans are being treated in a way which can be outright dangerous.

As a publisher today, how do you view your responsibility in publishing material with racist stereotypes and language? And what, from your understanding and study of Milton Caniff, would you say were his viewpoints on utilizing racist stereotypes, and the people he was creating stereotypes of?

As a writer, editor, and student of comics history, I gauge the merits of the material. I balance those merits against my perceptions of its shortcomings. I then use my knowledge of history to assess those shortcomings – do they stem from systemic creative failures, or are they shaped by the societal forces at work during the times in which they were created? After all, popular entertainers don’t make a living if their work doesn’t resonate with the contemporary audience. And what is often forgotten in modern assessments of decades-old comics is that the majority of work the artform has produced was never intended to or expected to have longevity. Comics were a disposable medium – the newspaper comics pages were expected to line bird cages; once they arrive on the scene, most believed comic books were fated to be tossed in the trash bin or burned up in stoves as fire-starter. Very, very few comics creators paused long enough to give social issues a great deal of thought.

Let’s put cards on the table: there’s some uncomfortable reading in those earliest Terry and the Pirates strips. At the outset, Caniff was not yet thirty years old and was still meeting commitments on the job he would leave (the Associated Press comic strip Dickie Dare) while beginning to develop Terry. He leaned heavily on stereotypical Asian tropes. While today we might view that with distaste, audiences in 1934 were far more sanguine about such depictions – after all, there was no direct satellite feed from Beijing or Shanghai into their homes. What most Americans knew about China came from the occasional newspaper or magazine news article, or from Sax Rohmer’s Fu Manchu stories, or from The Good Earth, Pearl S. Buck’s 1931 novel. And by the way, census figures show that ninety percent of the American population during this period identified racially as “white.” Many of them had no personal contact with those of Asian heritage; many of them knew little or nothing about life in the Pacific Rim. They were willing to accept what was presented, and it would have been easy for Milton Caniff to continue to feed them a steady, simplistic diet of racial “typecasting.” Did he do that? He did not.

To his credit, Milton began an ongoing study of Chinese society and the Chinese people. As his knowledge grew, his characters of Chinese heritage likewise grew in stature, complexity, and dimension. That process of maturation is most evident in the Dragon Lady, who starts as strictly a pulp cliché before growing to become a formidable military leader and fighter for Chinese freedom. If Connie could never fully escape his exaggerated appearance and fractured English (though note his English is far superior to Terry or Pat’s command of the Chinese language), Milton at least dulled his “comedic relief” role by giving Connie a level of resourcefulness and loyalty that his Caucasian friends recognize and reciprocate. By the War years, Connie had become an officer in the Chinese army. Compare him to other Asian comics characters of the period and I believe it’s easy to see Caniff was invested in depicting Connie as a person, not a one-dimensional, convenient stereotype.

I conclude my text piece in Volume 13 with a section titled, “Terry in Context: Viewing the 20th Century Through 21st Century Eyes.” Without excusing Caniff for falling short of the mark we now deem proper when depicting Asian characters, I try to provide evidence that we should recognize and credit him for coming closer to that mark than many of his contemporary creators, not just in comics, but also in radio, motion pictures, and prose fiction.

And remember the truism Santayana put forth: “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.” It’s a slippery slope to seek to expunge the sins of prior generations by ignoring past works that may be flawed, but which have compensating merits. Terry and the Pirates is a work that displays a considerable number of virtues while increasingly making an effort to “play fair” with its characters and its audience, given the constraints of the society in which it was produced. We can learn from and be entertained by its considerable strengths without applauding its subtextual shortcomings.

That’s a healthy and helpful chunk of information regarding Milton Caniff and other cartoonists of the time, and his evolution as a creator among his contemporaries. It brings me to a couple of follow-up questions for you regarding the disposability of comics, specifically in relation to choices made at that time regarding race. I love Terry and the Pirates as a work, but I can’t recommend it to people in 2021 without first explaining the comic’s racist slurs, caricatures and stereotypes. Having an informed knowledge of what’s in a piece of material, not just from its historical context, can help people make more informed decisions for themselves and what they share with others.

You have the ability to provide a great deal of context for readers, as you are one of the few people in North America who curates these comic strips for current readers. With that in mind, I’m going to focus on Connie as an example, as he is the most egregious stereotype in the series.

Caniff’s research and understanding of China grew over time to a more respectful and understanding treatment of its subjects, as did his treatment of Connie, but that core element of caricature and stereotype in Connie’s character did not change – even though the disposable nature of the strip meant that the ability to return to older strips was not part of a reader’s experience. The people who cry foul on behalf of a continuity error did not exist in the same way they do today, and he was free to draw as he saw fit.

Chester Gould of Dick Tracy said, paraphrased, that his job was to sell newspapers. Caniff certainly did so without using Connie as a central character in every strip, and without creating additional characters who had that same function or aesthetic. He did not need to make the changes he did in growing and evolving the Chinese setting of Terry as a whole, but he did, either to better sell his work or for his own personal pleasure. But within those changes, Connie was never given the overhaul that would have kept him from looking or sounding like a racist caricature.

There were multiple solutions that fit with the realizations Caniff made over time and with the strengths of the comics medium – to change Connie’s appearance outright between strips, to give him a short off-screen hiatus before returning with a new design and speech pattern, to change the character slowly over a series of strips and end with a new design, or to remove the character completely.

While the first three options would have changed his design, unless Connie was nothing but a collection of racist stereotypes – and it is my opinion that he was not – the character, his personhood within the story, would have remained.

Is it a reasonable assumption, then, to say that the uncomfortable reading that you refer to – where racial slurs were thrown around so casually, among other things – which later faded from the strip, could have similarly taken effect in regards to Connie without losing who he was as a character? Is it reasonable to say that as it stands, the character is ultimately a racist one, regardless of the changes Caniff did make to the character, by way of those core racist elements never being removed?

And finally, as readers, publishers, comics fans – how do we accept, and then act on, the racism which is present in the medium?

I think, in order to offer a meaningful response to your question, I need to set the stage with a few questions of my own (don’cha hate it when someone does that?).

Do you know how many people lived in the U.S. during the time Terry and the Pirates was originally published? Fewer than one hundred fifty million (150,000,000), versus today’s roughly three hundred million (300,000,000).

And out of that much-smaller American population of the early 20th Century, do you know how many identified in the U.S. census as “white”? Just about ninety percent (90%).

Finally, how would you characterize the mass media landscape of that period? As I previously mentioned, there was no satellite communication, no twenty-four-hour news cycle, no internet connectivity, no social media. Never mind streaming services, DVDs, or VHS – television itself had yet to make its presence felt. In Terry’s day, radio was the most immediate form of mass media, print was capable of the greatest longevity (the public library was a thriving part of most communities), and motion pictures made the most vivid impressions – “the talkies” were not even a decade old when Terry debuted in 1934.

OK – given that information, and given that, as I previously mentioned, most Americans knew little to nothing about China, it’s fair to ask: was Connie “racist” in the audience’s eyes, or was he initially viewed as the sidekick who adds humor and whose presence serves as “shorthand,” an ongoing reminder of the story’s setting, the way Margaret Dumont reflected stuffy High Society for the Marx Brothers and Smiley Bernette reflected the Wild West for Gene Autry? (Depression-era audiences probably knew as much about the Wild West and High Society as they did about China, after all – they went to the movies and read comics for escapism, not to muse about societal issues.)

If there were complaints from any readers about Connie’s appearance, they were so small in number they didn’t “move the needle” for Caniff – so why would he invest time and effort revising a character design that effectively no one was griping about? That sounds like a great idea eighty years down the line, after decades of social evolution; it wouldn’t be a sound return on investment in the moment, when deadlines relentlessly loomed, time was needed for research and for promoting the strip, and at least a semblance of a personal life had to be maintained.

The perspective you eloquently present also seems to assume Caniff had carte blanche to do whatever he wanted, which was not always true. In our Terry Master Collection Volume 13, we cite indications that Caniff, as a new employee of the Chicago Tribune New York News Syndicate, designed Connie under guidance from syndicate head Captain Joe Patterson. I’ll leave folks to read Volume 13’s “Terry in Context;” each person can make up his or her own mind concerning how compelling those indications are in terms of the latitude Milton had or didn’t have when he was designing Connie.

All this said, you ask, “Is it reasonable to say that as it stands, the character is ultimately a racist one …?” I’d say today, viewed exclusively through a 21st Century sensibility, it is possible to reach that conclusion. I’d also say that since the audience of the 1930s and 1940s did not react the way a modern audience reacts, it’s something of a Mugg’s game for today’s readers to expect Milton Caniff to have worked to standards other than those in existence at the time he was producing Terry and the Pirates.

I’d also sound a cautionary note about this line of thought: any number of modern-day news stories make it clear that 21st Century society has a long way to go before it achieves the Moral High Ground. It’s impossible to know how history will view the early 2000s, so to steal a line from no less a source than The Sermon on The Mount, “Judge not, that ye be not judged. For with what judgement ye judge, ye shall be judged.”

While Terry and the Pirates didn’t take place in real time the way For Better or For Worse famously did, Terry did grow up throughout the course of the series, from young boy to military pilot. Even the genre changed from a picaresque to a military adventure story. Why did the series change so much over the years?

Two words: Pearl Harbor!

America went to war the day after the Japanese struck Pearl, killing almost two thousand, five hundred Americans and wounding over a thousand more. These casualties were not just servicemen, they included several civilians – eyewitness accounts of that day on Oahu discuss how Japan’s planes were machine-gunning cars on the island’s highway. The comics went to war, too, and no strip did so with more realism and vigor than Terry and the Pirates. Caniff was perfectly positioned to place Terry Lee right into the heart of the war in the Pacific theater, and he modeled one of his fly-boy characters, Colonel Flip Corkin, after one of his real-life Army aviator friends, Lieutenant Colonel Phillip G. Cochran.

Do you have a section of Terry and the Pirates that you’re particularly fond of, whether it’s artistically, story-wise, or as a matter of personal preference?

That’s like asking an uncle, “So, which of your nieces and nephews do you like best?” (!!!) I love all of Terry unreservedly, but I suppose if I could read only one slice of the strip, I’d choose the five years from 1937 to 1941, from the introduction of April Kane to the end of the Raven Sherman saga. It’s mighty tough for me to zero in more specifically than that.

Milton Caniff said in a 1945 interview that comic strips were a Scheherazade form of storytelling, never to end. But he left Terry and the Pirates in 1946 to create a new strip, Steve Canyon, and seemed to break his own rule in that final sequence. Do you think that Caniff’s time on the series is a finite and complete narrative today?

Oh, I don’t think Caniff broke his “rule” at all. He didn’t own Terry, the syndicate did, and the syndicate’s Powers That Be hired artist George Wunder hired to succeed Milton. That meant Terry continued without missing a beat for more than a quarter-century after Milton left. Milton left Terry in 1946 in order to fully own his own strip, Steve Canyon, and he continued that series for forty-one years, until his death in 1988. In each case, then, I’d say the “Scheherazade form of storytelling” was in play.

That said, Milton took pains to weave his major Terry plot threads into a satisfactory conclusion – his final Sunday page remains one of the most impressive and justly-lauded accomplishments in comics history. He created a logical, emotionally-engaging pause in the narrative that allowed George Wunder to choose any number of ways to continue the series. It was that professional courtesy and respect for the material that helps make the Caniff Terry and the Pirates such an outstanding self-contained continuity.

The first release is slated for January with Volumes 1 and 13. What is the release schedule for the other volumes?

Actually, The Master Collection launches in March, 2022. Volumes are then released every four months, three volumes in a given year, using a March/July/November cadence. That means we’ll complete the series in the fourth quarter of 2025.

What is one thing you wish you could tell people about Terry and the Pirates that no one thinks to ask you?

There is a school of thought among some students of comics history that says Caniff never allowed anyone to assist him on any of the artwork that comprises his run on Terry. No one ever asks me where I stand on that idea. While I agree Milton did not use an assistant to regularly help him with the art chores (the way Chester Gould did on Dick Tracy and Al Capp did on Li’l Abner, for instance), I’m of the opinion Caniff accepted a little help, here and there, specifically from the great artist Noel Sickles.

Caniff and Sickles were fast friends. They shared a New York studio together in the mid-1930s, early in their careers. When Milton and his wife moved out of the city in 1937, Sickles was at first a regular visitor and eventually a full-time boarder in their home (the 1940 U.S. Census lists him as the Caniffs’ lodger). Deadlines were a challenge for Caniff throughout his career, and while he was always dedicated to delivering the highest-quality product possible, with an artist as skilled as Sickles at hand, I find it unrealistic to believe Noel didn’t help ink select elements in at least a few daily strips. In support of that belief, I point to the March 11, 1939 installment, the original of which hangs on a wall in my living room. The trees in the background of the final panel in that strip sure look like Sickles’s work to me!

None of us were there, which means none of us can truly know – we call ’em as we see ’em. But in this case, that’s how I see ’em.

And so concludes my interview with Bruce Canwell. An informative, thorough, earnest interview about a subject that he is clearly passionate about. It was also frustrating to see one of the most important issues in comics today be brushed aside. What you think of his answers is, of course, up to you. But I have one more point to make.

As he was so kind to bring up a Biblical quote, I thought I might finish it for him. From Matthew, 7:1-5, King James Version.

1 – Judge not, that ye not be judged.

2- For with what judgement ye judge, ye shall be judged: and what measure ye mete, it shall be measured to you again.

3 – And why beholdest thou the mote that is in thy brother’s eye, but considerest not the beam that is in thine own eye?

4 – Or how will thou say to thy brother, Let me pull out the mote out of thine eye; and, behold, a beam is in thine own eye?

5 – Thou hypocrite, first cast out the beam out of thine own eye; and then shalt thou see clearly to cast out the mote out of thy brother’s eye.

If one looks at this as the motes and beams of racism, I have worked hard to cut, to splinter, to pull and remove as much as I am able to. To say that I have completely removed ‘the beam in thine own eye’, to remove the racism inherent in living as a white person, is simply false – I will never deal with the racism that exists on a day-to-day level in many people’s lives. I cannot know what I cannot see, because, indeed, that is part of such a beam.

It is curious, and telling, that one would present a small piece of that quote when confronted with the question, “What do you know and do to help remove the motes and beams from other people’s eyes?”

If you wish to purchase Terry and the Pirates: The Master Collection, you can visit the following links. All Amazon links are affiliated, and help support reviews and interviews like this one.

Amazon: https://amzn.to/3s6BkL9

Clover Press: https://cloverpress.us/collections/terry-and-the-pirates-the-master-collection

For other Milton Caniff items of interest, check out the following links.

Milton Caniff’s Male Call – https://amzn.to/3yfeF0a

Milton Caniff’s Steve Canyon Volume 1 – https://amzn.to/3oHcJtS

Caniff: A Visual Biography – https://amzn.to/3EG6pbD

Meanwhile… A Biography of Milton Caniff, Creator of Terry and the Pirates and Steve Canyon – https://amzn.to/3DzLnKE

[…] be a problem after my interview last year with editor Bruce Canwell, well before I got the books. You can check out the interview here, but here’s a quick refresher on how that […]